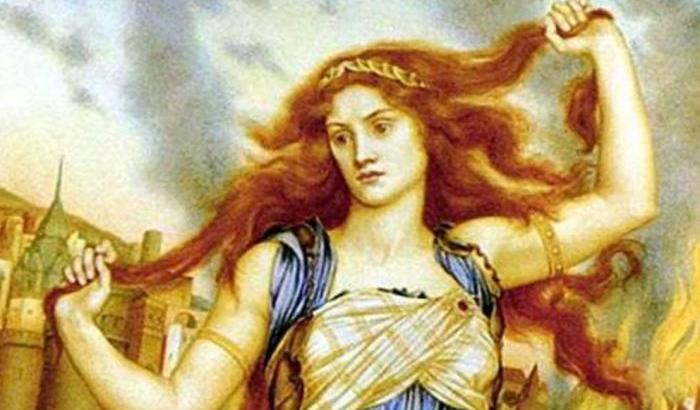

The myth of Cassandra, Priam’s most beautiful daughter, helps us understand how information works. The story is well known. It happened that Apollo fell in love with Cassandra, whose name in ancient Greek means “the one who entraps men.” We do not have precise information about how the facts – if there are any – developed precisely.

It is said that Cassandra spent a night at Apollo’s temple, knowing that the god was craving her. She refused to concede herself to him, reportedly. To seduce her, the amorous god presented Cassandra with the gift of prophecy, which the girl enthusiastically accepted and tried to use thereafter. Soon enough, Apollo realized Cassandra did not intend to sleep with him. As revenge, the vicious God did not revoke the gift but put a curse on her so that nobody would believe Cassandra’s predictions any longer. A key (though often overlooked) issue of the story is that Priam’s daughter never renounced foretelling, no matter how frustrated she was by not being believed.

Most of the time, the beautiful Cassandra is portrayed as a sad and tragic heroine, cruelly punished by a rancorous god. In fact, disclosing what later proves true adds to one’s posthumous reputation no matter how much they have been mocked when alive. On the other hand, we may also suspect that Cassandra had some minor responsibilities since wooing and accepting gifts is never totally innocent. In a version of the myth, she even promised to marry the god and then withdrew. If Apollo behaved just as any arrogant male chauvinist, Cassandra, nonetheless, was flattered by Apollo’s gifts and longing.

Cassandra’s myth can be read as a metaphor for writers and scholars flirting with power. As long as they belong to a ‘divine’ organization, they profit from the privileged condition of knowing and interpreting the key facts. Moreover, all people speak about what these writers and scholars utter. Writers not only utter the truth, but they also create it.

In this position, their egos swell, and they might begin thinking that people believe them because they are bright and tell how things indeed are and should be. They might even imagine themselves principled and incorruptible since they become oblivious to their initial flirting. They misperceive that their ability to elaborate important, timely, and witty arguments was a deal rather than some generous gift from gods (whoever they are). Writers and scholars who flirt with a demanding god may soon be smitten by power. They find freedom of speech irresistible and enjoy it when everybody listens to them preaching.

In a more sophisticated version of the myth, while Cassandra was sleeping (alone) at the temple, snakes licked her ears clean so that she could hear the future. This metaphor is easily interpreted: god’s snakes may allow someone to know what ordinary people do not, but this does not necessarily imply that they are allowed to spread information. Thus, journalists and writers understand what’s going on. They can confidently foretell what will happen because they are the unaware tools of building a future chosen by others. As soon as they foresee a diverse future, they are cursed by gods claiming the right to select a future they can control.

As for Cassandra at Apollo’s temple, the time came to choose between purity and stepping in with the god; in the same way, writers are requested to choose between freedom of speech and the gratification of being listened to. If they choose the former, they won’t be believed anymore; should the writers choose the latter, they will be requested to report nothing else but God’s voice.

If writers and scholars hadn’t flirted with power, they would have kept pure, but they would have never known the arcane secrets in the citadel of command. Cassandra would have never been awarded prophetical powers if she had not entered the temple and opened it to Apollo’s hopes.

You can either be pure and silly or corrupted and officially knowledgeable. Tertium non datur, the fallacy of the excluded middle. If you are well informed and pure at the same time, you create a danger, and gods need to put a curse on you. Cassandra’s tragic story teaches that by flirting, you might lose both power and innocence so that the knowledge you have acquired – that you imagine as a formidable weapon to affirm the truth (and your ego) – is transformed instead into a torture you use against yourself lifelong.

Therefore, remember, writer! You are in a trap: flirting with power lets you know how things go. If you eventually do not lie with a god, nobody will ever pay attention to you. You can be listened to and believed only if you are Apollo’s lover, but you will only be permitted to speak god’s rule.