What we could become in a more resilient world

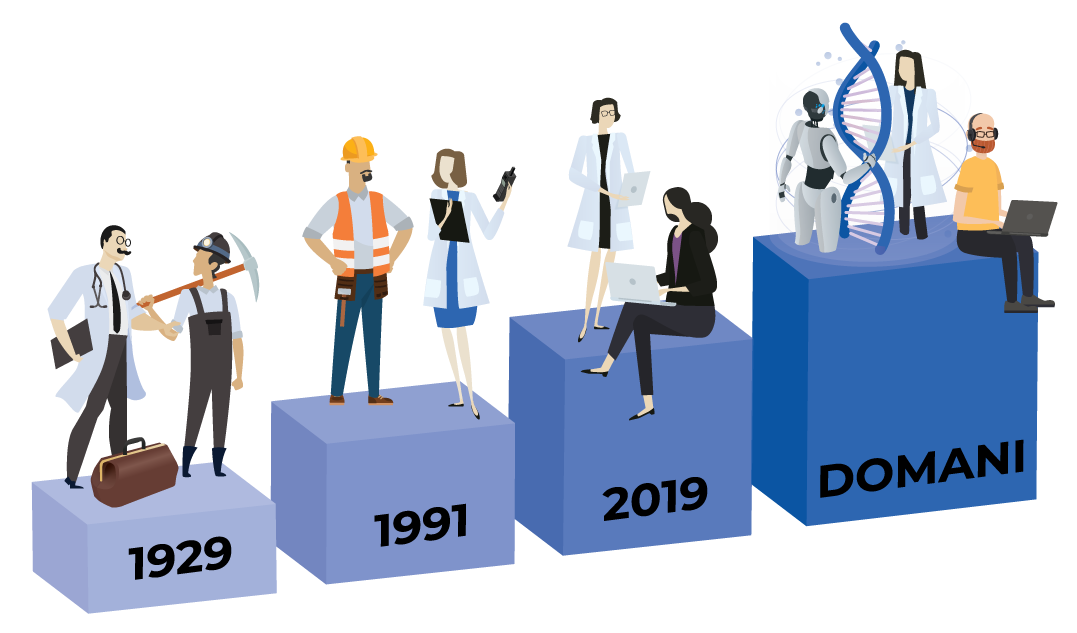

Notwithstanding all these damned restrictions, we need to stay positive. Not about the virus! We must think how to transform the crisis into an opportunity for further progress. This is a recurrent commonplace, sorry about that, but there are good reasons to repeat it. As US senator Cory Booker reminds us, the corona virus crisiscan expand our moral imagination. We are “resilient”. I need to use a word I heard for the first time in English, after the Twin Towers attack, and later after Hurricane Katrina. It’s an old term that Bacon and Descartes used in Latin (“resiliens”), and has since been included in specialised languages, such as materials science, psychology and ecology. More recently, social sciences have adopted this old neologism (sic!), and the media have followed. “Resilience” describes the capability of a social and economic system to react to catastrophes by absorbing them, bouncing back to the preceding state, and even making a leap forward. The Latin word “resiliens” means to rebound, recoil, jump back. Nowadays, “resilience” is a synonym of hope.

There are more serious problems in the world than the coronavirus: wars, hunger, climate change. We endure the daily carnage of car, home and work accidents. Covid-19 is different: it is an organisational global calamity, which we must cope with all together. The geography of health has erased all borders and revised the relations between states and populations. We are becoming more aware of social injustice in our health care systems, which affects human welfare even more than any specific disease. The COVID-19 pandemic will result in social research never seen before. Experiments trigger scientific progress in natural sciences, but mass testing is hardly possible in social science research, and rarely allowed in normal times.

That is why change and progress are slow and contradictory, except when a serious crisis occurs, such as the coronavirus infection. We are learning to keep physical distance from each other. You may notice people exaggerating, keeping as many as ten metres from each other. We see this in the Italian region where I live (Venetia), an area already inhabited by hygiene-obsessed people. Our supermarkets provide masks and disinfectant, so that everyone washes their hands before and after shopping. We are advised to wash even the outer packaging before opening food products. If I were an investor, I’d buy shares of hygiene products and pharmaceutical companies.

Perhaps the most important challenge to our resilience is the widespread use of remote work and meetings online; they will become even more routine than they already are. We could have adopted this new working style a long time ago, but we have prioritised personal interaction. Old regulations, trade union inertia, and technology aversion have made us prefer the good old style. We now realise that we do not need to move from one place to another to comply with most of our duties and errands. All this might hasten two major changes that have proceeded at a very slow speed: mobility and traffic; housing and construction. We can be much more active than we believed by just sitting in our living room in front of the screen. Hence, we can drive less, and the demands on our mobility infrastructure will not be as urgent as many citizens and (who knows why?) the construction lobby petulantly claim.

We may not need new roads, new rails, bridges and highways, so much as more electronic connections and nicer neighborhoods. Investment should go in the direction of facilities and infrastructures that reduce the need for mobility, such as e-commerce, home delivery, 3D printing, and remote work facilities and organisation. It’s not necessary to shut down what we have been used to. We all hope that soon we’ll go back to catch up with friends at the café and restaurants; go to the office just to meet the colleague we like or deal in person with the boss for a pay rise; see our students and talk with them face to face; and so on. But we’ll find out that all this can be reduced by something between 10 to 50 percent, depending on the job, on individual preferences, and on the role of personal interaction. Spending more time at home implies wider participation in neighbourhood life. City form and urban design will change. Paradoxically, remote work might improve proximity, as well as civic and personal relations.

Remote education is another possibility that technology offers to change lifestyles. Students can listen to online classes and meet with the teachers and professors just a couple of days per week. They can choose the time to open the class file and organise their days as they prefer, and so can the professors. The rigid, militaristic educational system might become more flexible. If the students move less, the cultural life of the place where they live would also be affected. Would such a restructuring be an improvement? Who knows? Certainly, we’ll realise that routines can be different. A major transformation is likely to occur in the health care systems. It is crystal clear that they are not prepared for pandemics. Only now we realise that, if this has happened, another pandemic – even more lethal – could take place in the future. COVID-19 shows us how the elderly, a large proportion of the population, are very fragile. We need to clarify ethical principles about how to manage such large-scale emergencies and priorities. Many observers claim that the obligation to stay at home will provoke a conspicuous rise in divorce and domestic violence. No; resilience will bring the spouses together and enhance family life. Wives, husbands and children will have more time together and will learn to listen.

On a lighter note, extramarital affairs are likely in much greater danger than marriages. Given the logistical, health and legal issues, unofficial partners will feel neglected, and jealousy will grow exponentially. As a consequence, the overall number of couples will not vary substantially.